COVID Tokyo Transit

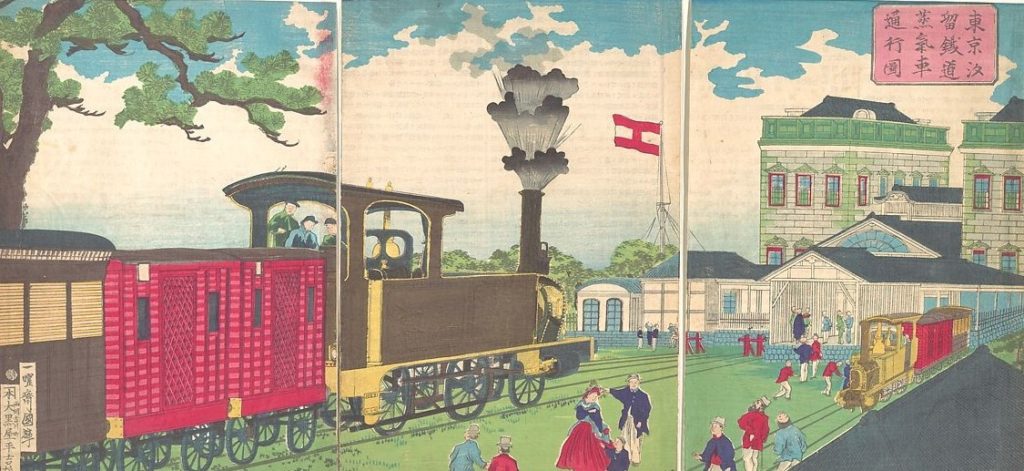

Illustration by Utagawa Kuniteru (Japanese, 1830–1874)

I LOVE THE SUGGESTION OF THE COVERT in the word COVID, hidden as it is in every corner of our paranoia. En route from Tokyo back to the U.S., it is all the things that are missing that demonstrate its near presence. No flights were leaving from Tokyo, as I found out on arriving at the hauntingly abandoned international floor at Haneda, where a dozen impeccably dressed attendants in blue serge and pantyhose stood at attention in the empty hall. Japan Airlines, fully staffed and at the service of an imaginary public. It is a quality I have come to love about the Japanese, a fundamental faith in all that is abstract and symbolic. They are serving, whether or not there is anyone to serve is a whole other question. When one of the young women there saw me walking toward the empty gate, she approached me like you would a wounded animal in the wild, tentatively. London, she said hopefully, No, I answered. Chicago. She pointed to the sign showing the cancellation that had been made a few hours before. Because of the virus, she offered, as if perhaps I hadn’t heard. Do you need to leave today? I do I explained, my visa expires tomorrow!

Haneda Airport, Tokyo, April 2020

My visa was about to expire, but more importantly so was I. I’ve been in Japan for the last three months, doing curriculum consulting for an international school by day. But after work I lived in arid loneliness, left in my tiny studio apartment/tomb to contemplate the endless failures of my sixty years with no one to contradict me. I looked for solace in Japanese literature, a fool’s errand if there ever was one. I read a lot of Death Poems, (a genre known as jisei in Japanese) and Basho. But even the Narrow Road to the Deep North got too narrow. I plowed through decades of Japanese stories, unrequited love, fire and suicide, until I too was ready for the same ending. One story in particular, Hell Screen, by Akutagawa haunted me. In it, a famous painter subjects his models to all manner of torture in order that he might paint more accurately the suffering of the Buddhist Hell Realms. Of course, he takes it too far, and in the final scene, with a flaming carriage that contains his beloved daughter, he too is forced to experience the worst thing he can possibly imagine. It’s an exquisite piece, and perfect for these times. What is the worst thing we can imagine? Staying home alone, or dying, or something in between?

In Tokyo we went on with life up until last week. I sat in cafés and restaurants reading of American friends in lock down, my son sending me pictures of boarded up San Francisco while I sent him pictures of crowds on the streets of Hiroo. Stories were circulating about why Japan was being spared, was it simply their acceptance of disaster, tempered by their knowledge of the earthquakes, fires, and bombings that had decimated the city time and time again and yet here it was.

The concerned agent listened attentively as I described my visa situation, I could go to San Francisco, Atlanta, LA, I explained. Final Destination, she asked? Seriously I wanted to say? Death darling. But I didn’t say it. She took from her breast pocket the hand sewn ivory notebook and fine tipped pen that every Japanese person is born with and asked me the name of the City of the Final Destination. Charlotte I said, she tried to spell it Sharlote, no I explained. Ch, as in Chicago. That was confusing, ch I kept repeating, sh, she kept writing, and for a moment it seemed like the vagaries of English spelling were going to be the real issue after all, as the random nature of this spelling rule brought immediately into play the random nature of all things that are unknowable or anomalous. What is the actual issue at any given moment, it is all in constant and unknowable flux isn’t it?

You get that headache and know that you have it and you’re going to die, and really you just don’t want to do it in a foreign country, I mean death is enough of a foreign country. But the headache turns out to be nothing and you go out for a latte instead, realizing there is so little evidence for anything we think. It is interesting, that now we do get to live in the inherent emptiness of all things, as the Buddhist would say, in all its rising splendor.

Meanwhile, my agent was still searching for a way to send me somewhere else. She led me across the empty lobby, to a chair, where she felt I could wait more comfortably while they searched. I took the chair as a bad sign. Look, I said, I’ll go anywhere in America. I’ll deal with it from there. I know how to drive.

The Japanese like simple designs but they love complex plans. The itinerary they came up with was so complicated that I thought they were joking, though it turned out they were exactly right. I would fly to one airport in Osaka, where I would then get a bus to the another airport 60 miles away and then from that airport, Kansai, I would get a flight to LAX and from there eventually a flight would leave for Charlotte. And with a few delays in between, it worked. I got to fulfill the fantasy of stretching out across the free seats of the empty jumbo-jet, dozing comfortably as we made our way across the night, across the ocean, thinking of the endless depths that are always around us, waiting for our notice.

Barbara Roether is a poet, novelist, and educator who has lived and worked in San Francisco, Morocco, Bali, and Tokyo. Her novel This Earth You’ll Come Back To (McPherson & Co., 2015) was winner of an Independent Press Award and a finalist for Foreword Magazine‘s Indiefab Book of the Year Award in Literary Fiction. A poetry collection, Saraswati’s Lament, was published in 2019 by Wet Cement Press. Her website is barbararoether.com.