So many facets to Dalí. I’m always writing haiku about Dalí. Different thoughts come to me about Dalí, and one thought came to me, that Dalí used to be very pretty, very good-looking. Garcia Lorca fell in love with him. When pretty-boy Dalí outgrew his pretty-boy looks he became “clown Dalí.” I’m no longer a pretty-boy, I’ll be a clown. The waxed moustache. The poses. The outrageous statements. You know his outrageous statement about the minotaur? “The minotaur is the clitoris of the mother!” I think he got it mixed up with the unicorn.

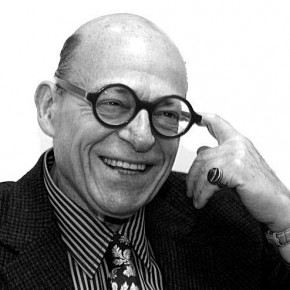

—Charles Henri Ford

* * *

My Brush with Dalí

by Duncan Hannah

In the winter of 1974 I was a 21-year-old junior at Parsons. I was often trying to gain access to the glamorous parties that were thrown by record companies, book publishers and movie studios for the free booze and celebrities. I somehow managed to cadge a pass to Interview Magazine’s Valentine’s Day party, honoring Geneviève Waïte, the petite South African ingenue with a new LP called Romance is on the Rise. A black-and-white poster of Miss Waïte graced my college dorm wall, she wearing nothing more than a man’s Swiss-dot tie, under the bold-type “Top Banana Joanna.”

I went to the party in my one good suit (black velvet YSL), got very drunk very quickly, looked longingly at the guest of honor, laughing with her husband John Phillips, formerly of The Mamas & the Papas. I remember a very large pink ice sculpture of a heart, which melted as the evening wore on. I knew no one but stayed on, availing myself of the open bar.

A chic European blonde approached me and said, “Why are you so drunk?” She dragged me over to a couch and introduced herself—Amanda Lear (born 1939), who had graced the cover of Roxy Music’s For Your Pleasure LP (1973), holding a black panther on a leash, while my hero Bryan Ferry, in full chauffeur livery, looked on, grinning. I had also seen Miss Lear in a nude layout in the French men’s magazine Lui. She was rumored to be a transsexual, though it was impossible to tell from the photos.

Anyway, she told me she worked with Salvador Dalí, and asked if I would pose for a picture he was working on. I’d be an angel. It would pay $50, which seemed a fortune. I drunkenly agreed, and scrawled my phone number on a matchbook.

The call came. I was summoned to the King Cole Bar in the St. Regis Hotel to meet Amanda and Salvador. I arrived at 5:30 in my good suit and leopard tie, and found Amanda at a small round table in the very crowded, noisy bar. I ordered a scotch and soda, and she scolded me playfully about being so inebriated at our previous encounter.

Just then a figure filled the doorway. The man with the mustache himself. He spread his arms wide, unfolding a gold cape, and with great dramatic affect, shouted, “DALÍ…IS…HERE!” He waited as a hush fell upon the stunned businessmen and tourists. Complete silence. Dalí spotted us, and strode through the tables like a gilded Dracula. Amanda rose and they kissed cheeks, while his bug eyes fixed on little me, quaking in my chair.

“Salvador,” she drawled, “this is Duncan Hannah…he is to be your angel.”

He pulled his head back, and with a fierce look said, “But wait! Do you have any hair on your chest?!”

“Uh, no, I don’t, Mr. Dalí,” I replied nervously.

“Ahhh, this is good… Dalí does not paint angels with hair on their chest.” He smiled with relief. But then his face contorted again, and he said, in an accusatory tone, “But you are a professional model?”

“No, sir, I’m not.”

Again a smile. “This is good. Dalí does not paint professional models.” Further concern crossed his animated face. “But what is it that you do?”

“Um, I’m an art student,” I returned.

A look of supreme satisfaction swept over him, and raising his arms, he said, “Ahhhh, then you LOVE…DALÍ!!”

“Oh yeah, we’re all crazy about you down at the art school,” I lied. (Dalí’s name was never mentioned except with derision.)

Dalí beamed with the confidence that he reigned supreme. Only then did he sit down, jabbering to Amanda in a mix of French, Spanish and English, never again directing his conversation to me, but occasionally glaring at me in what I presumed to be his artistic manner. I studied his cape. It had actual dead bees sewn into it. Wow.

He had no time for a drink, he had to meet his wife, Gala, so made a theatrical exit for the benefit of the punters, and was gone.

Amanda said, through her fire-engine-red lips, “Well, that went well, darling. Now come up to my room while I change for dinner.”

Not knowing exactly what this might entail, I said okay.

We took the elevator up to her room, small, dark and luxurious. She began bustling about with her wardrobe, toying with me, the “innocent” caught in her web. I tried to appear nonchalant, taking a seat and lighting up a cigarette.

The phone rang. It was Bryan Ferry calling from Toronto. Roxy Music was on tour, and he was checking up on his fiancée. She would repeat to me what he was saying, laughing in her husky voice. Ferry, apparently, was becoming alarmed by my presence in her bedroom.

“Oh Bryan, don’t be like that, it’s just a pretty boy I found for Salvador…no…no…he’s just waiting while I change…no, Bryan…don’t be jealous,” obviously making the pop star squirm. Imagine, Bryan Ferry, my idol, jealous of me! It was too surreal! I felt for the poor guy. He deserved better than this. Amanda told him she had to go, and I could hear him spluttering as she hung up the phone.

“He’s such a silly boy,” she said dismissively. “Always jealous.” She eyed me like a cat considering her canary dinner. “He doesn’t have anything to be jealous of, does he?” she asked coyly.

“But now I must meet my friends. Come along, darling, we will continue this later,” she leered. I dutifully followed her out of the St. Regis, out into the snowy streets, saw her into a yellow cab, and gone. All things said and done, it was an appropriately surreal evening.

A few days later, on a Sunday night, I got a call from Amanda. “Darling, I want you to come up to my hotel and see me.”

I thought about the transsexual rumor. What did that even mean? A surgically made vagina?

“I can’t,” I said.

“But you MUST! My favorite movie is going to be on television, The Ballad of Cable Hogue, starring Kim Novak. I want to watch it with you, darling.”

“Um, I really can’t. I’ve got homework.”

“Homework!?! But this is AMANDA, sweetie! I’m counting on you. You’re not allowed to say no.”

Gulp. Moment of truth. I really didn’t want to be alone with this carnivorous Euro gender-bender creature.

“I’m sorry, Amanda, I really can’t. I’ve got a class at 10 o’clock tomorrow morning and this picture needs to get finished.”

She blew up. “All right…forget it, then…forget Dalí…forget the whole thing!” SLAM.

So much for being a Dalí angel. Years later I was reminiscing about NYC in the 70s with my friend Bart, and he brought up how he modeled for Dalí.

“You’re kidding! I was meant to do that, too. What was it like?” I asked excitedly.

“Totally weird. I went up to their suite in the St. Regis. There were lots of people milling around, a salon of Euro-trash. Dalí was on the phone and never got off. Turns out Gala is the one wanted the boys. She told me to strip and stand on the desk. I kept my Fruit-of-the-Looms on. She watched me, then said, ‘Now take those off and maybe masturbate a little for me, no?’

I got angry and said, ‘I’m not gonna masturbate for you, lady!’ I got down and put my clothes back on and demanded my $50. She wouldn’t give it to me. I stormed out. What a bunch of creeps! Apparently, Amanda Lear was procuring boys for Gala. Dalí didn’t care…he liked to watch. Yuck!” said Bart.

So, actually, no angels were involved. At all.

* * *

Not that at the time I’m about to speak of—a time when Salvador Dalí was familiar to New Yorkers (New Yorkers, let’s say, who looked at Life Magazine and discovered that the Surrealist artist was often accompanied by a handsome and presumably tame leopard)—not that I had achieved much of a career as a translator, but somebody at Revlon knew I would be capable of helping Monsieur Dalí through the sort of task that may have constituted Dalí’s daily bread: Revlon was launching a new perfume and somebody at Revlon realized that Dalí was the consummate person to name it. Apparently somebody decided Dali knew enough English to perform such a christening, although shepherding Dalí from his habitual New York residence, the Saint Regis Hotel on Fifth Avenue, to Revlon’s showrooms, also on Fifth Avenue, was likely to require more English than labeling that first sniff or whiff of an attar.

I waited, therefore, in the St. Regis lobby till Dalí descended to discover those talents which I supposedly possessed, and which it was soon clear that when it came to a leopard in a revolving door, only a Surrealist could master. Once outside, we crossed Fifth Avenue in a trice, and there we were at Revlon (a matter of no more than East Side to West), confronting a vast table crowded with flasks and vials of the nameless attar, but as the name-giver approached to give or take an identifying whiff, a dozen cameras exploded into a brilliant fusillade; Dalí concentrated on mollifying the consternated leopard; and only when the final salvoes faded into a successful silence, did he turn to the Revlon reviewing-stand and say, “Je ne vois qu’un seul parfum nommable. I call the new fragrance FLASH!”

Dalí and the nameless big cat vanished (I assume back across the avenue), and I never saw either of them again, though I shall never forget, many years later, in the course of translating some texts of André Breton, the Master Surrealist reminded us that the appropriate anagram for Salvador Dalí was, eternally, Avida Dollars.

—Richard Howard

* * *

Making It New: Essays, Interviews, and Talks

By Henry Geldzahler

ISBN 9780962798764

Excerpt from “Good-bye, Dalí”

Salvador Dalí’s death, like so much of his publicized life, is taking on a grotesque, even a nightmarish quality. Now in his eightieth year, an enfant terrible for as long as he could get away with it, Dalí has lost his wife and mainstay, the redoubtable Gala, and with her his congenital optimism in the face of all that came his way. A depressed and justifiably paranoid old man, shaky with Parkinson’s disease, he has retreated into virtual isolation in the beloved Catalonia of his youth, settled in an apartment adjacent to the Teatro Museo Dalí in Figueras.

For several years stories have been circulating, not about Dalí so much as about the Dalí industry; who has access, who’s in control and, naturally, where do Dalí and his wishes come into the picture. This uncertainty, which has given rise to so much speculation, has its origin in three concomitant conditions, all of which have operated in gear: the phenomenal commercial value of the Dalí signature; the death of Gala, who was the chancellor of the exchequer; and the physically diminished, spiritually exhausted Salvador himself, for whom the sabor for life has ebbed away.

A brief shot on the early morning news of Salvador Dalí leaving the hospital in mid-October prepared me for what I would find in Figueras, Dalí’s native town, and Port Lligat, his chosen haven twenty miles away. Dalí, the magician, still active and in high gear in paintings made as recently as 1982 and 1983, was now in limbo. An inhabited shell with imploring eyes was all that remained. Dalí not yet dead, Dalí no longer fully alive—his ego felled, his curiosity wonderfully intact.

In 1926, at age twenty-two, Salvador Dalí was permanently expelled from the Instituto de San Fernando in Madrid by order of the King “for outrageous misconduct.” He had gone to Madrid to study painting; in disgrace he deliberately left his luggage behind, signaling a total break from his youthful past. In 1928 Gala, married to the French poet Paul Éluard, visited Cadaques and met Dalí, who was instantly captivated. “Without love, without Gala, I would no longer be Dalí. That is the truth I will never stop shouting or living. She is my blood, my oxygen.” In 1929–1930 Dalí painted Le Grand Masturbateur, directly inspired by his love for Gala, who by now was living with him. The landmark Surrealist film Un Chien Andalou was written with Luis Buñuel during this time.

Dalí’s acceptance in America was virtually immediate. In 1932, Dalí was twenty-eight years old. He had three paintings in an exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York. It is from this exhibition that The Museum of Modern Art, then three years old, purchased The Persistence of Memory, the famous melting watch that instantly became an icon symbolizing all that is bold, “psychological,” and up to the minute. It is, in a phrase from its decade that has never been bettered, that Freudian will-o’-the-wisp, THE HAND-PAINTED DREAM PHOTOGRAPH. In 1941, on the brink of America’s entry into war, The Museum of Modern Art gave Salvador Dalí a large retrospective exhibition, his first. The text mentions several times his scandalous reputation that has been talked about for a decade.

Dalí’s writing and statements throw a screen around his art, obscuring and illuminating sometimes in the same paragraph. He is brilliantly amusing, deliberately obfuscating, and, finally, supremely worth the trouble it takes to shuck the corn to its delicious meat. He has always claimed that he doesn’t know what his paintings mean; at the same time he has also hung the most extended, involuted literary-psychological meanings on them. “Be persuaded that Salvador Dalí’s famous limp watches are nothing else than the tender, extravagant and solitary paranoiac-critical camembert of time and space.”

Like James McNeill Whistler and Oscar Wilde before him, Dalí makes verbal perverseness and a dandy’s aestheticizing stance and garb his signature style. Everything he says is calculated to shock us into thought; he questions your assumptions with the humor of a true hysteric. “What I hear is worth nothing. There is only what I see with my open eyes and, even more, what I see with them closed.” “One thing is certain, I hate simplicity in all its forms.” “Each time someone dies, it is Jules Verne’s fault. He is responsible for the desire for interplanetary voyages, good only for boy scouts or amateur underwater fisherman. If the fabulous sums wasted on these conquests were spent on biological research, nobody on our planet would die anymore. Therefore, I repeat, each time somebody dies, it is Jules Verne’s fault.” It isn’t only about his own work that Dalí can scintillate. He embroiders explanations of life with so much nonsense and true enigma that we are consistently caught off base. No wonder Harpo Marx is one of his heroes.

“But I myself am living, and I will live without ever liking jazz or Chinese sculpture. I have never been a pacifist. I have never liked little children, or animals, or universal suffrage, or modern art, or El Greco, or theosophy.” Sometimes sounding like an auto-intoxicated, highfalutin W.C. Fields, Dalí, along with Picasso, stands apart from his generation of artists; dismissed as a charlatan by the popular press, and, consequently, by the public. Charlatan is, of course, a left-handed tribute. What rarely is noted, however, is the unlikelihood of an intelligent and passionate adult acting the charlatan, much of the time alone in his studio, sixteen waking hours for as long as fifty years. If it were possible—what a hero of consistency the charlatan would be: how admirable!

The Gallery of Modern Art, in the underrated Edward Durrel Stone building in Columbus Circle that now houses the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, was the unhappy dream of A&P heir Huntington Hartford. His retardataire and vehement hatred for all that was modern in art, especially abstract painting and the Museum of Modern Art, so agitated him that he took a full-page ad denouncing both in the New York Times. In his Gallery of Modern Art he made his case by exhibiting work by artists that were anathema to doctrinaire modernists; the English Pre-Raphaelites, Burne-Jones in particular, the French academic painters, Bougereau and Meissonier, and, among contemporary masters, Salvador Dalí, the only artist he collected in depth to have a retrospective exhibition at the enemy bastion, the Museum of Modern Art. Dalí’s espousal by the know-nothing Hartford polarized opinion about his work and he was cast for the first time since his excommunication from the Surrealist movement by André Breton in the role of the anti-contemporary, an extreme position that was belied by his continuing admiration for Picasso, Miró, and such Americans as abstractionists Barnett Newman and Willem de Kooning. A story is told about Dali’s visit to the great encyclopedic museum in Cleveland in the mid-sixties. Asked what he thought of the collection, Salvador Dalí is reputed to have said, “What kind of shit museum is this, with no Barnett Newman?” Both Dalí and Newman, at the time, were colleagues in the stable of Knoedler’s art gallery.

I met Salvador Dalí and Gala in 1962 at a small dinner in Marcel Duchamp’s townhouse apartment on West 10th Street. Duchamp had seen me in a Claes Oldenberg Happening in the East Village several months earlier. The evening entertainment, two related Happenings entitled Ironworks and Photodeath, called on me to assume several roles. I alternated between sitting quite still and making extreme facial expressions at the public seated only a few feet from the room designated the “stage”; and I wrote with a big pen on a scroll when suddenly a piece of black velvet dropped on me. As with all Happenings, nothing was explained or susceptible to explanation. For many years, Marcel Duchamp had been a chess-playing chum of my boss, Robert Beverly Hale, the first curator of American Painting and Sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum. Duchamp, always curious about art and the vanguard, invited me to dinner as a potential source of information. I had been at the Met for a few years and, of course, admired Marcel Duchamp enormously. I was a bit shaky but delighted to be at his table. The Dalís’ presence was an added fillip. French, with Salvador Dalí’s exaggerated and charming Spanish accent, was the evening’s language. Well over an hour into the dinner Duchamp asked me what was going on, in Happenings, Pop Art, underground film—the whole range of New York artistic activity. I gave as thorough an account as I could on the spur of the moment, waxing enthusiastically on the subject of Jack Smith’s film, Flaming Creatures, in Dalí’s mouth the almost undiscernible FlaaaahMeeng Cray-a-tooo-Rrrressss. It was at this point that Gala Dalí noticed me. She turned to Duchamp while I was speaking to ask him WHO I was. He explained and she announced in a loud voice, Pour moi il n’est pas expert, For me he’s no expert. Inflated by Duchamp’s attention, deflated by Gala’s rudeness, I passed a memorable evening.

Another meal I had with Salvador Dalí took place on the top floor of the Gallery of Modern Art, the Gauguin room (named for the two unauthorized tapestries after his South Sea paintings). Seated opposite Dalí, I found myself suddenly shy under his watchful glare. We chatted in French and English and, at the end of the meal, he asked me to visit him in his studio at the St. Regis Hotel. I was happy to comply; he continued to fascinate me as an artist and as an amazing contemporary presence, a wild man who had once jumped out of the window at Bonwit Teller in an event planned to publicize his art. A few days later I made an appointment through his long-time personal secretary, Captain Peter Moore. Dalí’s startling revelation at this meeting was that he wanted to do a sculpture of my head in gold, with a moving tongue accurately modeled from life. I hesitantly asked him how we would come up with this unpleasant artifact? Dalí said casually, “You cast it from life. Bring it to me.” After consulting with a dentist friend in Washington, Dr. Teddy Fields, I unreluctantly abandoned the project. What second and third levels of satiric meaning may have been concealed in Dalí’s desire to portray me with une langue qui bouge, a moving tongue?

One evening a year later I gave a fundraiser for Julian Bond, an old friend from Harvard Square (in the summer of 1958). Julian was running for reelection to the Georgia State Senate. After dinner I took him with me to a party for Peter, Paul, and Mary at the St. Regis. I had known Peter Yarrow since high school and when we ran into each other in the lobby I introduced Julian Bond and Peter Yarrow. Suddenly the old Surrealist of the St. Regis, Salvador Dalí himself, advanced on us, a flush of excitement on his face; “Come up to my studio and I will show you the most rrreeemarrquable objet of the twentieth century.” Sweeping my friends along with me he led us into the elevator, an oddly assorted crew taking off on a daring mission. I did what I could to introduce everybody, each with a tag line, for example, he sings, he writes laws, he’s a Spanish painter. We got to the studio, the door slammed open, and there! under a white sheet! in the corner! stood the most remarkable object of the twentieth century, discovered that very day by the zeitgeist himself! Dalí with panache and grace whisked the sheet away and there stood an eighteen-inch-high rubber incarnation of !!!!!! LE BOOGS BOONEY, splattered through his chest and tummy with paint freshly squeezed from the tube with utter prodigality. Yes, Bugs Bunny, the Woolworth version, stood in all his leering innocence, under an inch or so of rapidly applied color. Pop Art, I guess, had met with Action Painting; a new icon for our times was the result. Needless to say we were severally amazed and no one, to my knowledge, has ever heard of Le Boogs again.

Dalí adores Art Nouveau architecture and decoration. In Barcelona, one senses the influence of the city on his waking dream, especially in Antoni Gaudí’s use of stone as a medium that can droop and melt, that can, as it does in his masterpiece the Cathedral of la Sagrada Família, aspire to heaven in the fashion of gothic architecture, at the same time as it metaphorically dies and rots into the earth, dripping like the wax candles that are everywhere for sale in Barcelona’s gothic quarter. Dalí takes Art Nouveau architecture so seriously that early on he wanted to pursue his identity with it to the point of eating it. One thing about Salvador Dalí, he always goes the extra mile.

Dalí himself first conceived of a museum for his hometown, Figueras, as the first example of true Surrealist architecture, a building that would express his art, his humor, and his take on the world. The art that would hang in the building was to be his collection, what he admired and wanted to share with his public. The town officials of Figueras were adamant that without Dalí’s own art in preponderance, there would be no Dalí Museum in Figueras, and, surprisingly, given the track record of municipalities on questions of art, they had the right idea. The Dalí Museum, officially the Teatro Museo Dalí, a large building with four crowded floors and a huge courtyard, is a museum in the traditional sense, a former grand residence filled to brimming with Dalí’s drawings, paintings, sculpture, and prints. It is, at the same time, Dalíesque in the extreme; crowds of Catalans and a heavy sprinkling of foreign tourists swarm through it, amazed, impressed, and, at some exhibits, elbow-nudgingly giggly. At several points in the museum the public is urged to stop to look through the telescopes at what becomes, at a proper distance, a portrait of Abraham Lincoln, or in another, an arrangement of furniture in a large room that reads, through a framing device, as the face of Mae West. Works from every moment in Dalí’s career are unsystematically arranged, with no information, no titles, and no date. Refreshingly Dalí-like, it rhymes with the old magician’s nose-thumbing at the official art world and its self-importance. The people, his audience, need only Salvador Dalí—he communicates directly without apparatus. Dalí said it best in 1981; speaking of a catalogue of the collection at the Teatro Museo Dalí, Dalí pronounced that it must be “hypocritical, in a manner to trouble people’s spirits.” “It is necessary that all the people who come out have false information.”

I had read some of Dalí’s rhinocentric musings in the art magazines, and, needless to say, found them hard to fathom. One day in the mid-seventies I got an invitation to join the Dalís for lunch at a now defunct restaurant, The Baroque, very near the St. Regis. When I got there, Tom Hess, the editor of Art News, and several other guests were already seated at a round table in the almost deserted dining room. Dalí instructed us, when Gala swept in about fifteen minutes later, that we were all to stand at our places and applaud her as she approached the table. Puzzled but game, we did as we were told. Lunch, after this off moment, progressed much as usual. The only other untoward incident was impelled into action by my chatting with the lady to my right—Gala, wielding the weapon-like pasteboard menu, cracked me smartly on the head, with a Moi je suis aussi, I’m also here! Ignoring the blow as best I could, I took forceful advice and chatted with her. After the dessert and coffee, before anyone could leap to leave, Gala shushed us all and Salvador Dalí announced that this very morning he had written the most important art-historical article of the…century…I think it was. He was going to read it to us in his amazing Spanish-French-English, and, the event that began the meal, our applauding Gala’s entry to the restaurant, was echoed perfectly by Gala insisting that, as Dalí read his piece, we all applaud politely until he finished. What little I can remember about the content of that day’s lecture was concerned in some way with Vermeer and the rhinoceros horn, an ancient aphrodisiac in the civilizations of the Mediterranean.

The “Dalí question,” how good an artist is he, how much of his work and words are to be taken seriously, has always preceded and hounded the enigmatic Catalan. Has he been the court jester of painting in our century? Has he used Surrealism as a theater of techniques, ideas, and images for his own aggrandizement? These “Dalí questions” have never been answered definitively; we are still too close to the phenomenon of his personality to know what is meat and how much is sauce. If he has been a jester (a noble role in the Renaissance hierarchy) has he, like Lear’s fool, addressed his puns, visual and verbal, at higher truths?

I think the answer is yes, with the qualifier that the higher truth has always been profoundly autobiographical. This program, which ties all Salvador’s art and explanations to a single logic and value system, has been so savagely adhered to, so openly the single subject of his life’s musings, that, unable to take the son et lumière that has attended his morbid self-absorption, we have been tempted to shrug and smile at much of his infantilism. The great question that hounds all artists and their posterity, will the work survive the artist’s absence, the death of his personality, is asked with particular urgency in Dalí’s case and accounts, I believe, for the constant sandstorm that roils the air when the man and art are considered seriously.

In his fascinating but infuriating spiritual autobiography, The Unspeakable Confessions of Salvador Dalí, the artist spends the greater part of the book making every effort he can to gross us out. As a very young boy, Dalí tells us, “My shitting habits, I must say, were not without charm, either. I always tried to think of some perfectly unexpected place: say, the living-room rug, a drawer, a shoebox, a step on the stairs, or a closet. Then I went about it discreetly. After that, I ran through the house proclaiming my exploit. Everybody immediately rushed to discover the object of my elation. I became the leading character in the family play. They grumbled, they yelled, they lost their tempers as time dragged on. I tried preferably to select a time when my father was around so he could see it happen, if not be involved himself. One day, just to make things better, I dropped my doody in the toilet. They looked everywhere for the longest time, but no threat would get me to reveal the place I had chosen. So, for days on end, no one dared open a drawer or set foot on a step without worrying about what they might come upon.” All the essentials of the Dalíesque drama and call for attention are present in the microcosm of this noisome vignette. Salvador the magician turns dross into gold by making its discovery the object of a “treasure” hunt; hiding it somewhere else each day gives an inconsequential story endless permutations, surprise endings and, at the same time, keeps the action close to home and in control. The fact that almost all the drama takes place in Dalí’s own mind is yet another constant with his artistic strategies.

The adoration he accords Gala, his elder by a decade, almost from the moment he meets her in 1928, at age twenty-four, is the keystone of his bid for maturity, or rather for the “normalcy” always beyond his grasp. A masturbator until he meets her, his mother-twin, he finds in her his paradigm for heterosexuality; on first seeing her back, “Gala was there, sitting on the bench. And her sublime back, athletic and fragile, taut and tender, feminine and energetic, fascinated me as years before my baby-nurse’s had. My most daring action was to graze her hand so I might feel the electric shock of our mutual desires. I had no other intention than to remain eternally at her feet.” Pre-verbal, touch the sense that turns him on, how like a little boy!

From the perspective of 1984 Dalí’s achievement is mixed, but, on the whole, more positive than we might have thought a decade ago. In spite of Modernism’s continued hegemony over the visual arts in this century, we see another vein that goes straight back to the nineteenth century and Dalí’s much-admired French realists Meissonier and Bouguereau; their highly polished and technically breathtaking art had its parallel in every national style of the late nineteenth century. It now seems obvious that the public’s slightly salacious adoration of this art, so despised by Modernism, has continued unabated and found popular expression in photography (the Marilyn Monroe calendar) and sharp-focused film. Love of the recognizable, the enemy of total abstraction, is more tenacious than we thought. The human need to “see” the familiar, and to feel oneself at the center of the universe, remains amazingly seductive and perhaps even talismanically necessary.

Seen in this context Dalí’s special brand of Surrealism, concocted as it was from de Chirico, Tanguy, Miró, Arp, and Ernst, as well as from the Spanish and Dutch seventeenth-century still-life painters, jolts us anew each time we return to it for the very reason that the disorienting visions he constructs so convincingly, the soft bones on crutches, the putrefying cadavers and the melting watch, speak at one and the same time to our secret dreams and fears and our guilty love for the precision and shiny glow, the fin-de-siècle rot, of sentimental realism. Dalí’s most successful work introduces new subject matter, dream matter released by Freud, in a most comfortingly rendered vision, his canny crutch for the soft viewer to lean on, to make the unbidden supportable.

It is impossible to think of another painter in our century who has cast as much pepper in the face of his public as has Salvador Dalí. From the beginning he has refused to be judged on his merits; he has taken pride in his ability to continue into maturity and beyond the infantile behavior that so shocked his parents. His credo may well have been, if it worked then, I’ll do it again.

Salvador Dalí, the naughty boy who shocked his parents and the King, is fading, but until his light goes out completely, let us not underrate his wit, tenacity, and flair. While alive, and even in his death no doubt, Dalí will always manage somehow to shock us one more time.