PREFACE

WHO have compiled these writings am innocent of any intention to defraud in offering them to a confiding and, I hope, forgiving section of lovers of English literature. If anyone is to blame for their publication, it is a friend who has himself written a book and has, time after time, emerged unscathed from a publisher’s office. This friend has assured me that “Kilreynard on Fox Hunting” would have a monetary value provided that the outer coverings were made sufficiently attractive to compensate the buyer for what he is likely to find within.

To this end I have devoted the best of my days, and, with an apology to Mr. Punch’s College of Arms, I leave it to the kind reader to say whether or not the result is eminently satisfactory.

The life-like portraits with which the treatise is embellished have not met with the unqualified approval of the celebrities they so strikingly represent. The danger and difficulty that an artist has to contend against in illustrating historical works of this kind can only be appreciated by those who try it.

Criticism has been not only adverse, but varied. In no single instance is a portrait admitted to be in the least like.

It has even been urged that whips are not depicted in the way they should be held. So trifling a detail as the omission of spurs has excited severe comment on the part of those who are portrayed, in spite of my assurance that they are safer without them.

It has been hinted that when it becomes known that there is no such nobleman as the Earl of Kilreynard recorded in the Peerage, the sale of the booklet will diminish to nil.

The Earl’s coronet, although merely symbolic, is an exact copy of the genuine article, which may atone for the deception as regards the mythical Earl. The Kilreynard family, I rejoice to say, is by no means extinct — on the contrary, it is full of going, and there are many to be found in the arena of sport to compete for the representation of that illustrious race.

As the kind and forbearing reader watches the charred remains of “Kilreynard on Fox Hunting” disappear up the chimney of his study, let him reflect that he has at least contributed to a good cause. The profits of the sale of this little book, if profits there be, are not destined to replenish the empty coffers of Kilreynard Castle. They will be offered to the Hunt Servants’ Benefit Society instead.

C. W. B.

October, 1899.

Arms- Quarterly.- 1st In dexter chief on a road sloppy, a sportsman sergeant and caparisoned, anathematising a horse fresnèe and full of beans; emblematical of the song called “The place where the old horse shied.” 2nd. Over a bar sinister charged and fracted, a thruster taking a toss proper into a field starry. 3rd. On a field chequey, a park of hounds courant, painstaking to the last. 4th. Out of a cabbage bed vert, a sturdy Briton rampant grasping a toss fork gory. Motto: “Let ’em all come.”

FOX HUNTING.

THE origin of this scientific pursuit is so remote that it may be said to be lost in the dense mist of antiquity, but that the sport of fox hunting existed in pre-historic ages there can be no doubt whatever, as there is no evidence, either documentary or otherwise, to prove that it did not. When or where the first fox was hunted and killed by hounds has never been determined by the Masters of Foxhounds’ Committee. But it is to be hoped that in the interests of science and morality no pains will be spared to throw light upon so important a question, and decide it for good and all. So far, every scrap of evidence that has been adduced by the various hunts in support of their claim to this distinction has been proved by the author to be utterly spurious and misleading.

There can be no question that the glacial periods of the dark ages proved most disastrous to the interests of fox hunting when we consider the discouragement that five thousand or more years of unbroken frost would cause even the most enthusiastic devotee.

It becomes necessary to draw upon our imagination if we would contemplate a pre-historic fox hunt. Bearing in mind the conditions then existing we are led to conclude that the sport was conducted in a very crude and primitive fashion, but it is interesting to discover traces of these savage methods in the behaviour of the “fields ” in the present day we find the most open season on record, the like of which we must hope will never be seen again. Then it was that the patriarch proved himself to be the staunchest fox preserver of either ancient or modern times. The circumstances of his foresight are too well known to require further mention in these pages. The debt of gratitude that we owe to him is universally acknowledged by modern fox-hunters.

It has been suggested that fox hunters of those ancient days never wore any distinctive garb as they do now. In fact many authorities affirm that no garb at all was worn by those primitive thrusters. This may or may not be true. We hope not, or, if it be true, that ladies were not so interested in field sports as they are now. In the present day every fox hunter must be attired in the acme of sporting fashion or else he must forego all claim to being a sportsman. Even in the non-hunting season an indescribable “something” must dominate his personality if he wishes to maintain a reputation as a “hard man to hounds.” What that “something” is the author does not profess to know, but it must be present all the same. The secret lies buried in the bosoms of the members of Boodle’s Club, and we believe that it is known also to Messrs. Lock, the well-known hat manufacturers of St. James’s Street, who for centuries have been bound by a most solemn oath never to divulge it.

As recently as two hundred years ago every established pack of hounds hunted both fox and hare, but now the fox only is regarded as legitimate quarry.

The author has observed that foxhounds do not always appear to share this view or to adapt themselves readily to the new order of things. When a hare gets up before them they invariably show that she is by no means a thing beneath their notice ; in fact they relish the change ; whilst, on the other hand, a student of human nature would discover that the huntsman did not. The love of variety is strongly marked in the foxhound character, whether it be in the choice of food or quarry, and the author has frequently enjoyed a fine burst with hounds after nothing better than an ordinary sheepdog ; but this form of sport has not yet gained the measure of popularity that it is entitled to.

Since the days of Peter Beckford great changes have taken place in the ways and methods of hunting a fox. The custom of the ancients was to leave their hounds entirely alone when once settled to their game ; only under the most exceptional circumstances did they venture to offer any assistance, preferring to throw the hounds upon their own natural resources. This antiquated idea bore its own fruits, and resulted in foxhounds and harriers acquiring such an independence of character and self reliance that it has become almost impossible to break them of it, and so meet the requirements of the present day. Sometimes the greatest difficulty is experienced by hunt servants in driving hounds from the line in order that a talented huntsman can make the cast that he desires.

So popular has the sport of fox hunting become that an intelligent interest in its pursuit is aroused in the minds of all those who have actually participated in it, and in those who have not. Books on the science of venerie have been written and widely circulated (as presentation copies), with the result that it is difficult to find anyone who does not know more of the theory and practice of fox hunting than anyone else. Earnest, nay even heated, discussions as to how hounds should be “handled,” coverts drawn, and casts made are of frequent occurrence in the hunting field, making the duties of the professional huntsman a matter of ease. Antiquated ideas as to the movements of a flock of sheep, the carrion crow, or jay being an indication as to a fox’s movements have long since vanished. Except as a means of exercising hounds in the summer time, sheep no longer take a part in the game of fox hunting, whilst the crow and jay are as scarce as the proverbial Highlander’s breeches.

The position of Master of Foxhounds carries with it an exalted social standing ; that is to say, in the village in which the Master of Hounds may live. Should he be wealthy, he receives what is called the unanimous support of the town and neighbourhood, more particularly, if possible, of the town, the saddler and corn dealer being prominent as his staunchest patrons.

A Master of Foxhounds in the present day should have certain qualifications, a few of which we will proceed to enumerate.

One great essential is that he should have a thorough knowledge of the requirements of the hunting public and be well posted in the law of trespass. Another, that he should know something of the habits of the fox beyond what he has learnt from the early perusal of Aesop’s Fables, particularly so if he aspires to be his own huntsman. He should have a fairly shrewd idea as to where foxes are most likely to be found, so as to be able to ignore the instructions of the keeper who is in charge of the covert that he may be about to draw. Again, he should know where a fox will go to when pursued by hounds. Failing this, the next best thing is the ability to maintain that he knows, whether he does or not. Some authorities affirm that a huntsman should not only know what number of hounds he has in his pack, but also their names, sex, and pedigree. So far as this we will not go, as it is quite unnecessary to address the individual hound. A handful of well- chosen names to make use of when occasion requires will suffice to all intents and purposes. To the canine mind one name is as good as another, sometimes better. The author is under a deep and lasting obligation to a valued friend for his permission to make use of an interesting document which was discovered in the archives of a neighbouring rectory. The very great antiquity of the manuscript, together with the lateness of the hour at which it was unearthed, made the task of deciphering it very difficult. Nevertheless, the author is able to put before his readers an extract which will prove both interesting and instructive.

Extract from “Advice to Young Sportsmen on the Arts of Venerie” (1400) :

“When thou purposest to deposit thyself in a portion of thy country where the coverts are small and the fences such as engender courage in thy companions in the chase, direct thy kennelman to draft for thee such hounds as bear titles as follows : Blaster, Blastus, Cursitor, Customer, Custard, Damager, Damsel, Damson, Damacene, Damodes, Damper, Damnable, Damosel (far away on, Damosel — try it). Or if thou goest into a hilly country, be thou thus prepared, for peradventure, when thou climbest nearly to the summit, and thy horse is scant of wind, thou wilt find comrades,who have ascended at leisure by a more circuitous route, eager to direct thee, with little apparent faith in thy skill or that of thy hounds. Footmen, again, may appear who, having lifted up their voices in the face of the fox, have caused him to retrace his steps, while they themselves are content to point thee onward and upward. Then, if thou ratest thy hound Blaster, or others of suitable title, even though they be not in fault, it will be to thee as when one bloweth froth from a mug of ale, and thy spirit will be lightened and comforted while thy conscience remaineth unburdened. If, through misadventure, no such hound be present it mattereth little, provided thou art ready to indicate without demur the hound thou hast mentioned, being careful that the sex agreeth to the name.”

From this it will be seen that the opinions held by the writer of the ancient manuscript are in complete harmony with those of the author of this humble treatise. Here and there may be detected a trace of grim humour, but the soundness of the old sportsman’s advice to beginners is unassailable. The author earnestly recommends the young amateur huntsman to lay to heart the vocabulary of hound names given — one and all will lend themselves to the tongue with astonishing readiness when he is actually in the field.

A knowledge of horseflesh is most useful to a Master of Hounds, although he should always refrain from obtruding it on his stud groom, to whom the buying and selling of hunters should be left entirely. The chief essential in this department is that the Master be able to preserve as good a balance at his bankers as he does on horseback.

Assuming that the young M.F.H. is ambitious to become his own huntsman, we strongly urge him to master the rudiments of equitation before undertaking the responsibilities which devolve upon the office. There are many highly respectable riding schools in London at which a few days’ attendance will ensure proficiency. All these establishments make instruction in the art of riding across country a speciality. Riding to hounds is undoubtedly an art. With some it is an inborn talent, with others it is not. More depends upon what is called “nerve” than anything else, and nerve implies indifference to the consequences of a fall. There are many brilliant horsemen who never know the meaning of danger, the author’s modesty forbids him to mention the best of them. Nothing is more enviable than the ability to ride straight after, if not actually amongst, a pack of hounds in full cry. As obstacles vary, so vary the methods of negotiating them. In riding at water it is impossible to go too fast. Impetus invariably ensures the rider’s arrival at the opposite bank, or near it. With timber it is different. This should be taken at a stand ; that is to say from the gallop to the trot, from the trot to the walk, from the walk to the stand. The arms and legs of the rider should play an energetic part in riding at all fences, and should the horse be clever, the rest may be left to him. Regaining the saddle after the leap is merely a matter of practice.

The drop fence should be negotiated with extreme caution, the left hand grasping the reins and mane of the horse, whilst the right keeps a firm hold on the saddle behind. When this kind of obstacle presents itself there is a good opportunity to perpetrate a harmless joke. Urge some short-sighted friend to “go on,” assuring him that it is nothing. Afterwards, when you have picked him up, you remark, in a jocular manner, that he appears to have had a “drop too much.” This is a fine witticism, and cannot fail to provoke great merriment amongst all present.

Seeds may be ridden over by the veriest novice, and no previous knowledge of fox hunting is required, besides which the feat is quite free from all danger, if practised during the absence of the agriculturist to whom the field belongs. The same may be safely said of the ewe pen, which, when hounds are not running, affords an opportunity of jumping that if sought for elsewhere might not be forthcoming.

A wheat field invariably has great attractions for hard-riding men in wet weather, particularly if a gap in the fence makes it easy of access. Jumping on hounds has more to do with the “field” than the master. It is a time-honoured custom, and, although unpopular with huntsmen, it holds its own as an amusement to be indulged in after a hunt breakfast. No particular skill is required, although some display greater dexterity than others. It should be effected without ostentation.

Roads and lanes next demand our attention. These are by no means despised by the majority of fox hunters, as the highest possible rate of speed may be attained on them, and when the hounds are casting down one or the other a favourable opportunity occurs for putting it to the test.

Doubles are frequently encountered after a hunt breakfast, and are quite unavoidable.

And now a word to the fair followers of the chase. The question of nerve in their case need not arise, for one and all have it in a marked degree. The hunting costume of ladies still bears a strong resemblance to what it was years ago. Although the Gainsbro’ hat and flowing skirts have long since been discarded for a more serviceable covering, a small portion of the former riding habit is still worn. In neckties there has been a revolution. In riding to hounds a lady cannot do better than select a bold and trustworthy pilot, after whom she should ride as closely as possible. Of course, should the pilot fall she is almost sure to do the same ; but if the pace is fast impetus will throw her clear of the struggling man and horses, when she must remount as quickly as possible and get a new pilot.

Let the author here warn his fair readers that to harbour a feeling of compassion for a fallen hero, be he never so handsome, is a weakness that should be scorned by modern sportswomen. To dismount and raise the unconscious head upon her lap, bathing the pale forehead possibly with eau de Cologne, is only worthy of the heroine of a sporting novel. The fallen thruster isn’t worth it. He is wholly devoid of sentiment, and nothing ever comes of it now, as in days gone by. Tend him, nurse him, watch over him as you will, when the fractured collar-bone is mended and the bulged-in ribs are better, he will be off, off like a butterfly back to the field, leaving behind him only a broken heart. And that won’t be his — no ; it isn’t good enough. Those who still doubt what the author has said would do well to consult some experienced mamma.

To those fox hunters who do not care to risk the danger of riding over fences, and yet do not wish to expose themselves to the ridicule of their friends, the author will give an invaluable hint. Let the rider be careful to exhibit the greatest anxiety to get a good start, to show that he really means business. Then, when he hears the “forward away,” he must cram down his hat as far over his head as it will go, at the same time vigorously applying the spur to his horse (whose tail should now revolve rapidly), and gallop away as fast as he can. This conveys a fine impression to all who see it. When the inevitable happens, and the sportsman finds himself in a field from which there is no exit but the gate by which he entered, he must assume a look of great determination. Catching hold of his horse tightly by the head, he should drive him at the thickest place in the fence. On arriving within taking off distance, the hold upon the horse should be suddenly relaxed. This will, in nine cases out of ten, cause the animal to refuse. These tactics may be repeated until the rest of the field have disappeared, when the sportsman can return to the road. Should anyone happen to be present, it is as well to flog the horse soundly, and denounce him as being a stubborn brute that has again lost the rider a real good thing.

The author trusts that these few remarks upon riding to hounds are concise, and that they will prove of value to his readers.

SOUND MANAGEMENT.

IT is not obligatory that a Master of Hounds should trouble himself with kennel matters or the breeding of foxhounds, because, as a rule, the pack belongs to the country, and is held in trust, as it were, by a capable and influential committee. They (the hounds, not the committee) vary in value from 2s. 6d. to £100 a couple. Should a young M.F.H. have to buy any, he may devote his attention to the cheaper kind, as they differ very little from the others in appearance and are easier to procure. In some cases they are extremely good looking. During the summer it is usual to hold what is known as the “puppy show.” This is a function that arouses the greatest interest in hounds and their pedigrees amongst the members of the hunt. In fact, but for the show it would be hard to discover that any interest at all was ever taken in such trifling matters.

Should the Master elect to avoid the anxiety and disappointment of hound breeding, he may easily do so without in the least affecting this popular annual gathering. A sharp huntsman will rise to the occasion, and will draft from the pack a suitable number of the freshest and best-looking hounds he can find. These will represent the “young entry” of the year. The Master will see that a neighbouring M.F.H. or two are invited to judge, and that a printed list of hound names, arranged so as to appear in litters, with the respective sire and dam, are distributed amongst the guests. If this is done properly and with ordinary care, a very creditable show may be held. Of course should one of the judges discover the ruse the Master would be in a very awkward dilemma, but this calamity is highly unlikely to occur. If it did, a rapid adjournment to the luncheon tent is the wisest move. There, under the beneficent influence of an unknown vintage, all will be forgotten and forgiven.

At the luncheon toasts are given and responded to, the Master, in graceful and well chosen language, welcomes all present at his table. The judges express themselves highly satisfied with the “young entry” ; indeed, if the huntsman has discharged his task of selection properly, they will most likely say that the entry is one of the best and strongest they have ever seen. The Hunt Committee will be much gratified to think that the destinies of their hunt are confided to the care of such an excellent Master. Speeches to follow are both numerous and varied. The Master toasts the judges and touches upon the masterly fashion in which the awards have been made. (Roars of applause from the prize winners, whilst grunts of dissent may be heard in other directions.) The oldest member of the hunt will speak in eulogistic terms of “the best Master they ever had,” while the Master himself marvels at the veteran’s perspicacity. Then follow the hunt servants. The huntsman goes straight to the point, declaring himself to be a man of but few words, deeds being more in his line. Given good scent, plenty of foxes, and no barbed wire, he can show sport, and means to. He resumes his seat amid loud yells of “Tally ho !” “Forward away !”

The stud groom next responds for his department. He says he does not wish for a better Master, who never interferes in any way. He loves his ‘osses better than his own children, and is always up at two o’clock in the morning. (Here some wag remarks, “But not in the stable, old cock.”) He will point out what a blessing his large establishment is to the farmers of the neighbourhood, from whom he always buys his corn, hay, and straw. (Loud cheers, with here and there hints that other hunting people might do the same.) This functionary’s oration will bring down a storm of applause from the underlings and strappers. The afternoon is generally spent in looking over his stud. If it is only a small one, the groom can spin out the day by arranging that the visitors shall see each horse over again in different boxes, by which, if there is plenty of stable room, the stud may be made to appear limitless.

In describing the good qualities of each horse, and what he has done, the Master will do well not to say that he himself rode the animals over seven foot of timber, thirty feet of water, or whatever it might be, but that he had given a friend a mount on that occasion. Hounds were running hard, when, happening to look behind, he saw his friend follow him over the greatest and most sensational jump ever known. It is the best way to put it, being modest, and showing a wish to share the glory with others.

The author will now ask his readers to imagine that summer, with all her dust and heat, has passed away, that a successful “cubbing” season has been got through, and that the regular hunting season has commenced under the most favourable auspices.

The hunt breakfast, or “coffee housing,” may be mentioned as an aid to riding across country. It is in fact one of the principal attractions of fox hunting, and its abolition would, in most countries, mean extinction of the hunt. It affords the shooting man an opportunity of dispensing hospitality to his hunting friends whilst his keeper is making arrangements for a “sure find” in the shrubbery.

Champagne, potent liqueurs, and other like beverages are consumed in large quantities at the hunt breakfast. Toasts are given and responded to; indeed, as a rule, this breakfast is a right merry meeting of the whole country side, and it brings people together who would not otherwise meet — people who are unable to leave home to get a “peep at the hounds” except when there is a breakfast. When cigars have been lighted a move is made, and the breakfast is over, except for the few who invariably find that they must have left their gloves under the dining-room table, and are therefore obliged to return. When these few have been again hoisted into the saddle by the butler and bystanders, they will give their horses a “pipe opener” over the tennis lawns in preference to cutting up the carriage drive.

Arrived at the covert side, the talented huntsman will carefully ascertain which is the way of the wind, and, having done so, he will give that matter no further consideration. The whips, whose duty it is to anticipate the wishes of the huntsman, which must vary according to the exigencies of the moment, will lose no time in assuming the most conspicuous positions they can at those points of the covert from which a fox would be likely to break. Entering the covert, usually down wind, the huntsman will cause a few of his hounds to draw for a fox by using animated and cheerful language, taking care that at least two-thirds of the pack are following closely at his horse’s heels. The language to which the author alludes is called hound language, because it appeals to the canine intellect as much as any other. It may be acquired by paying attention to those who already know it. Should it happen that a fox is in the covert, the hounds that find him will most likely “open,” that is to say, give tongue. On hearing this, others, if so minded, may join actively in the proceedings. Now that a fox is actually on foot, the huntsman, instead of standing aghast at the enormity of his responsibility, must ask himself the question, where will this fox go to provided he cannot be killed in covert ? The ” field,” by which we understand those who follow the hounds, are always able, and generally willing, to give valuable information and assistance on this point, but there are times when their help is not available, and the huntsman finds himself suddenly thrown upon his own resources. Then it is that he must prove himself able to act without hesitation — to grasp a situation, in fact (which is useful when he finds himself out of one), and get on good terms with his fox.

It often happens that a supposed find is nothing more or less than the catching of a hound in one of the many steel traps that are always to be found in well-preserved fox coverts, but there is a difference in the cry, which we shall more readily detect as our experience ripens. In the event of a hound being trapped, the Master will do well to ask one of the field to dismount and pacify the animal, whilst another releases him from the trap. Any stranger who is out for this day should have the opportunity afforded him of rendering this triflin service. Whilst this is being done the fox will be enjoying a merry time of it in covert, and the stranger will find that the task he has undertaken is both instructive and exhilarating- The Master need have no fear that the fox will get away, for the duty of heading him is gladly undertaken by the field, who, assisted by the ex-masters present, never fail in discharging it thoroughly to their satisfaction. Past experience always serves the ex-master in good stead. He generally knows fairly well where a fox is likely to break, and usually succeeds in reaching that point in time to prevent the animal effecting his object.

The rendering of this service is usually surreptitious, as it is better that the huntsman should remain in ignorance as to whom he is indebted.

There is no surer sign of a fox being on foot than the vociferous cheering of the field in the open. Quickly as possible the huntsman should collect his hounds about him and gallop to the spot from whence the cheering comes. On arriving there, he will be told that a fox has really been seen, but that he has retraced his steps in the direction he came from.

After saying a few well-chosen words of thanks for their information, the huntsman will re-enter the covert, blowing his horn. The hounds will soon recover the line of their fox, and “Tally ho, back!” from whips at various points will reassure the huntsman that all is right. Should a general stampede of the field ensue, the huntsman may take it for granted that the fox has at last broken away. The most prudent course for the huntsman to pursue is to gallop with his hounds in the direction already taken by the field, and should he succeed in overtaking them, he may at once ask which way the fox has gone. Provided they have not already captured the animal, they will readily give the information desired, and he will learn that the fox has been seen to go in four or five different directions. Having carefully cast for the points indicated by the field and failed to hit off the line, the huntsman may allow the hounds to try in a direction entirely the opposite. In a moment or two they will be running steadily and well.

It is affirmed by old-fashioned authorities that scent varies according to the nature of the soil upon which it is supposed to lie. Some will have it that on grass hounds may be cast very quickly, even at a gallop, under certain conditions, whilst on plough or fallow a cast cannot be made too slowly. The author emphatically disagrees. No one has yet been able to say what scent is. It is, and always will be, a mystery. Various opinions and theories as to its nature have been urged. Instances of its being visible to the naked eye, when burning in the vale, have been given, but investigation invariably proves them to be hallucinations. That there is such a thing as scent now and again we still believe, and we continue to hope that our faith in it may not be entirely shaken.

Should the huntsman now be satisfied that his hounds arc right, he may either let them alone or hold them on to the nearest fox earth and mark the fox to ground. But hounds have, in bygone days, been known to hunt and kill their fox without the slightest help, and it is to be hoped they can do it again. By attending to holloas and asking questions much may be learnt as to the condition of a hunted fox. A fox that has been hunted for some length of time is sure to have got his “back up,” which is not to be wondered at. Assuming that the huntsman thinks fit to mark the fox to ground, he must do as the author has already described. Marking to ground is an impressive and soul-stirring spectacle, and is generally a prelude to what is known as “digging out.” This method of killing foxes is extremely popular; in fact, some Masters prefer it to an}- other, especially late on in the season. Earth stopping (another very ancient sporting custom) is one of the chief aids to digging out. It is effected whilst foxes are underground by a professional earth-stopper, who receives payment for his services. Keen as the field are on other points, they never actually assist in digging out. Now and again some former M.F.H. may be seen to wield a spade, presumably more for the sake of the trifling pecuniary remuneration to which the service entitles him than anything else. Whilst digging out proceeds the field will have lunch, smoke and chatter, which is a great inducement for the fox to make a bolt for it. Most likely the poor fellow is engaged in expounding to a couple of terriers his view of the one-sidedness of the whole affair. Eventually he is got at and thrown to the hounds amidst great rejoicings, particularly on the part of the inevitable old lady who swears that he has killed over ioo chickens for which she has never been paid.

The author may mention the fact that in most hunts a custom of paying losers of poultry for what they have lost is supposed to exist. When claims are made they are dealt with by a committee of investigation, who are empowered to make ducks and drakes of a fund set aside for the purpose, and so recoup the losers in kind. The Master has nothing to do with this department any more than he has with collecting subscriptions, although he is likely to hear more of one than the other.

The author now realises that he has said all that is possible about the glorious institution called fox hunting. Should any of his readers consider that anything remains to be explained, or that their thirst for knowledge is not quenched, the author will gladly do anything that he can further to assist them.

AUTHOR’S NOTE.

SINCE going to press a telegram, couched in despairing terms, has reached the author from his publisher: “Please arrest continuous stream of enquiries, letters, and telegrams which are likely to inundate our offices.” The author, therefore, begs his readers to restrain their ardour pending the publisher’s removal into more commodious premises.

The author will now deal with the correspondence before him.

In reply to Chancellors of the Universities, heads of colleges, Sunday school teachers, &c, the author begs to say that it would be impossible for him to undertake a course of lectures on fox hunting in different parts of the kingdom.

In answer to the artists and sculptors who enclose designs for monuments in Westminster Abbey, the author can only say that he considers their suggestion to be slightly premature.

Lottie. — Yes ; your grandpapa is quite right in saying that your action in jumping on him when down was unsportsmanlike. We hope that the old gentleman is none the worse.

Spring Captain.— From April 1st to the season’s end would suit you best. 2. Very smart boots are made by the Oxford-street firms you name, and you could not do better. 3. No ; we have never found them press for payment.

Parish Cat. — Yes ; we certainly think that he ought to attend church on Sundays. 2. Although agreeing that everyone should take an interest in village matters, we do not think that you can reasonably expect a Master of Hounds to preside at the mother’s meeting, at least during the hunting season.

Economical. — Undoubtedly your old trousers would convert into excellent breeches if they are not too much worn. You should have white pearl buttons, six or seven on each side, about ii inches apart. Your regulation Wellington boots would do admirably. No; we have no old hats for sale.

Country Squire.— You can generally get one down from Leaden- hall Market in time.

Shocked. — You have been misinformed. We can assure you that the long frock hunting coat is not, as you imagine, adopted for economy’s sake. Breeches are always worn as well.

Diana.— We are very sorry to hear that your cob was viciously kicked by a horse wearing a red ribbon in his tail. No

doubt the rider spoke truly when he explained that the ribbon was not put there for ornament ; but he need not have so rudely told you that it was not intended to be eaten.

Materfamilias. — No; the Master got married last summer.

Amateur Huntsman. — We did not think it necessary to give instruction in such a simple matter as this. Most people know that the horn is blown from the taper end, not the bell. 2. No; we cannot account for the hounds running away from you when you blow the horn, our own experience being that they take no notice of it whatever, as a rule.

Distinguished Foreigner. — We heartily sympathise with you, and deplore that our remarks upon riding across seeds have involved you in so much trouble. We expect you did not see that they were qualified by the words ” provided the owner of the field is not present.” The weapon with which your injury was inflicted is called a pitchfork, and is very dangerous in the hands of a British farmer. W r e are glad that you like the hunt breakfast on account of there being so many ladies present.

Obadiah Stiggins. — We are sorry that you object to our treatise on hunting being introduced to the village library. Hunting and horseracing are two different things. What you have been told about Masters of Hounds spending their Sabbaths in cock-fighting, drinking, and gambling is untrue.

Leamington Spa. — No; you could not subscribe less than one guinea per annum to the hunt, seeing that you keep eight hunters and your wife and family hunt too.

Old Sportsman. — We are glad that our treatise meets with your approval, and we keenly appreciate your friendly intentions as regards the barrel of oysters and case of champagne. The Perrier Jouet 1874 will do splendidly.

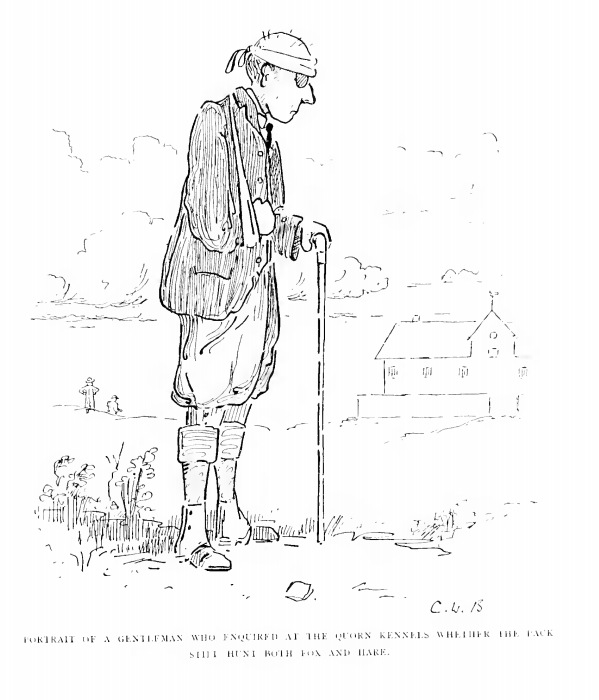

Traveller. — No; we do not think that the Quorn still hunt hare as well as fox. We would advise you to enquire personally at the kennels.

PORTRAIT OF A GENTLEMAN WHO ENQUIRED AT THE QUORN KENNELS WHETHER THE PACK STILL HUNT BOTH FOX AND HARE.

INTERVIEWER’S REPORT.

IT was 8.30 a.m. when I arrived at the Castle. Even at that early hour I found it besieged by a dense , crowd of interviewers and farmers with sticks. Having elbowed my way through this throng with great difficulty, to whisper the pass word through the keyhole was but the work of an instant, the ponderous bolts slid silently from their sockets, and the next moment I was within. From the ancient retainer I gathered that the Earl was already in the library, and that on receipt of the usual fee would grant the interview I desired.

Whilst the retainer descended to the coffers for change, I quickly made notes of my surroundings and their respective values. The hall was not, as I had expected, emblazoned with arms of many quarterings and ducal coronets, neither did the coat armour of the Earl’s ancestors startle me from the recesses.

“All them went to Wardour-street long ago,” explained the ancient retainer on his return. ” Beyond the coronet worn daily by the Earl, no trace of the former grandeur of the Kilreynards remains.”

On entering the library, I was conscious of being in the presence of a great man. A graceful neglige attire did not in the least detract from the calm dignity of the Earl’s personality. Adjusting the heel of a richly-embroidered carpet slipper, he rose to welcome me with the manner of a true-bred sportsman and scholar.

“I acquired my deportment in France, a few years ago,” the Earl kindly explained. “It is purely superficial.”

Going at once to the point, I begged the Earl to disclose to me the secret of his greatness. A smile of gratification spread over the Earl’s countenance.

“My greatness is not entirely of my own making,” he said, ” I share it unselfishly with others,” waving his hand towards innumerable portraits with which the walls were panelled. “In those,” said the Earl, ” lies the secret of my success. They are the portraits of the friends with whom the greater part of my life has been spent — all true sportsmen ; and,” whispered he, in a confidential sort of way, “the book on fox hunting, with which I have startled the world, is nothing more or less than the complete embodiment of the knowledge of the whole.”

For some moments I stood aghast at the magnitude of the volume. Anticipating the question I should ask on my recovery, the Earl pointed to a towel with which, although I had failed to observe it before, his brow was encircled. “Water,” said he, ” is one of the most powerful aids to mental effort, besides which,” he continued, “externally applied, it is a fine antidote.”

In reply to my question as to whether he ever used it for anything else, the Earl smiled, and, picking up a large stone which at that moment came crashing through the window, he advanced slowly towards me and asked me if I cared to terminate the interview. With a hasty good morning, I left him.

EXTRACT FROM LOCAL NEWSPAPER.

WE regret to say that while leaving the grounds of Kilreynard Castle, a few days ago, our valued reporter, Mr. Scrawley, met with violent treatment at the hands of an infuriated crowd that had assembled there, and is now lying in a precarious state at the Cottage Hospital. Mr. S. was of a most peaceful and inoffensive disposition, which leads to the conclusion that it is a case of mistaken identity.