Think of the great American surrealist Joseph Cornell (1903-1972) and consider the following description of a mysterious object – a wooden structure with glass in front, through which one looks upon a dream world of celestial bodies, La Belle Époque, the Romantic Ballet, the Grand Hotels of Europe and all the visual wonders from the seven seas. One might mistakenly assume the object described was a Cornell box, but this also describes another equally mysterious object that was treasured by the artist and was carefully studied for countless hours throughout his life. In fact this object had a formative impact on Joseph Cornell’s visual imagination from his earliest childhood. The artist’s father purchased this object in 1900, which was three years before the artist was born, but it became so important to Joseph Cornell that it remained in his possession his entire life. Before the artist died in 1972 he passed this object along to his closest confidant, his sister Elizabeth “Betty” Cornell Benton (1905-2000). She continued to gaze in wonder at its magical vistas, even after her eyesight had failed in her twilight years. When she was finally confined to bed she kept it on a bedside table within easy reach as a precious touchstone of their earliest childhood memories.

This mysterious object is Joseph Cornell’s stereopticon.

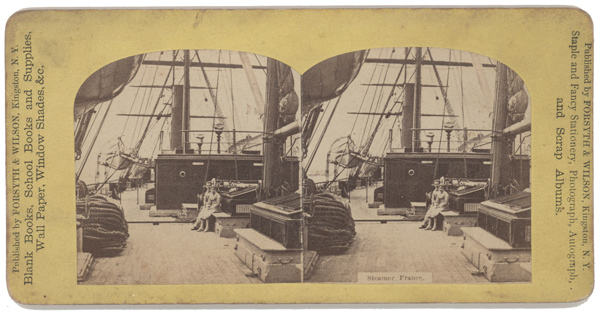

The stereopticon is an ingenious contraption that creates the optical illusion of three-dimensional photography. It is a wooden structure with two specially ground lenses, held with one hand close to the viewer’s eyes, while the other hand slides a focal rack, loaded with a special viewing card, back and forth to adjust the correct distance to create an astonishing illusion of three-dimension space. Every new stereopticon came with a small selection of viewing cards, which are mounted with two specially prepared photographs, but the owner was encouraged to buy many more viewing cards for a nominal sum.

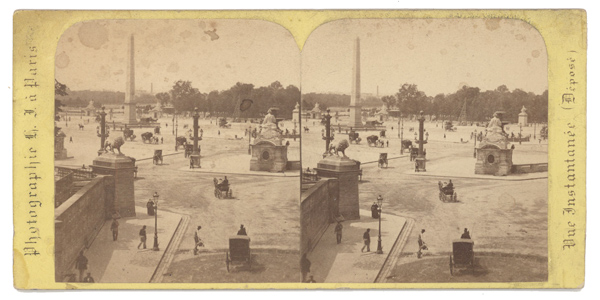

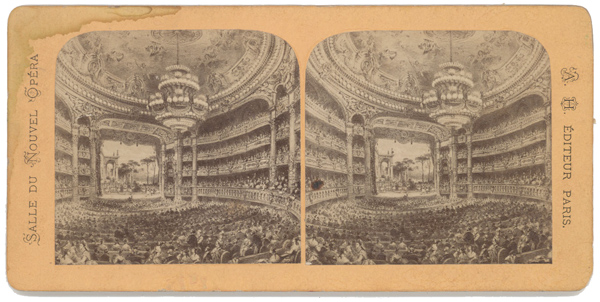

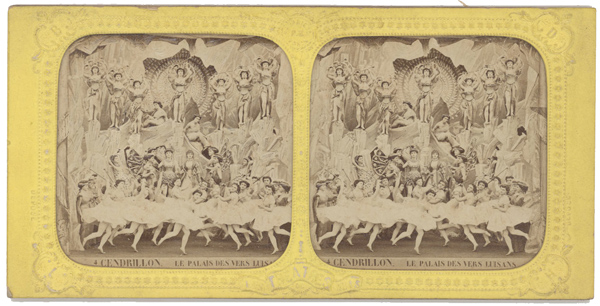

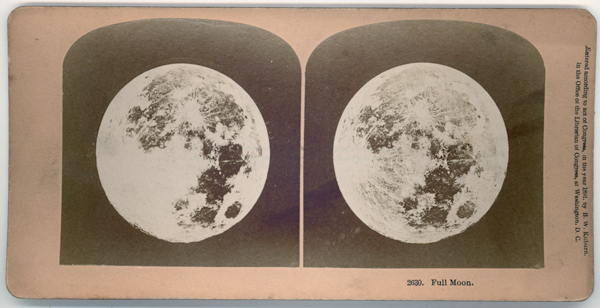

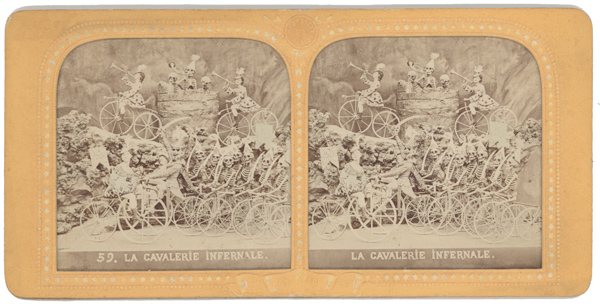

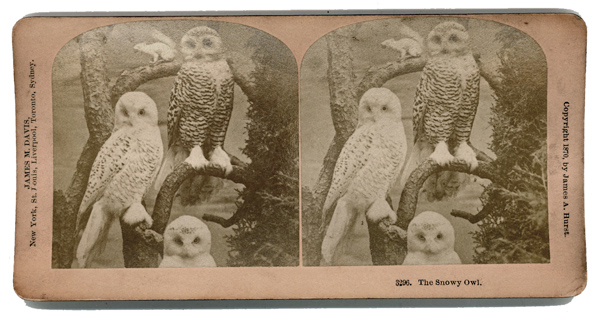

The stereopticon was the hottest-selling souvenir item at the 1900 International Exposition in Paris. Perhaps it was so popular because it reflected the many marvels of technology at the Fair, such as the Eiffel Tower, motion pictures, and sound recordings. Photography and rotogravure were still innovative media, so it was mind-boggling for visitors to see a stereopticon’s three-dimensional view of persons, places, and things that were previously only obtainable by a magic carpet ride. Naturally the younger generation of 1900 were thrilled to be on the verge of a new century in the Age of Invention with the promise of unimaginable wonders, so they embraced the stereopticon as a niftier amusement than old-fashioned parlor games, like tiddlywinks, hand shadows, and charades, because it harnessed new technologies to perform a magic act. There were as many different stereoscopic viewing cards as there were player piano rolls or sheet music of popular songs. The list of subjects was endless, from the capitols of Europe to the villages of Borneo, Presidents, popular celebrities, opera stars, ballerinas, dance hall queens and astronomical views of heavenly bodies, birds, bugs, volcanoes, floods and fires, as well as fantasy scenes of fairy spirits and demons. Competing manufacturers produced viewing cards of every conceivable subject, including some with hand-tinting or moveable parts and transparent papers to create even more astonishing effects. But the most popular scenes of all were viewing cards of the Paris International Exposition of 1900, which allowed the average earth bound American to enjoy the impression of having actually visited Paris.

The Cornell family lived in Nyack, New York. The artist’s mother was Helen Ten Broeck Storms (1884-1966). His father was Joseph Isaac Cornell, III, (1875-1917). Both families were of Dutch ancestry. Helen and Joseph met in Nyack in 1900, where they both lived with their parents. Although both families had once been rich import traders, their circumstances had grown rather less prosperous. Helen’s family took in boarders for extra income and Joseph worked as a salesman at a local dry goods store, which sold housewares, hardware, candies, sundries and novelty items, including a wide selection of stereopticon viewing cards.

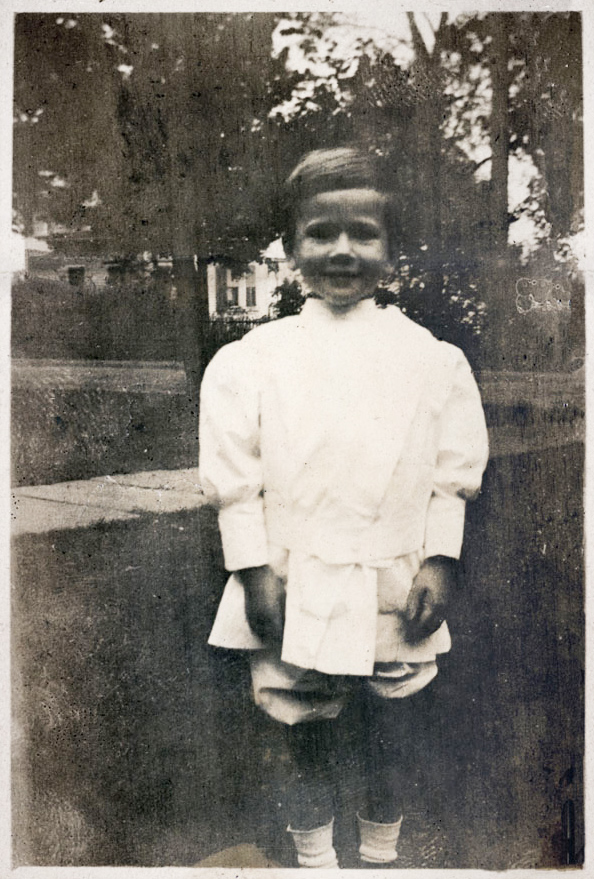

Joseph Cornell’s parents married in 1902 and moved in with her parents at 128 Piermont Avenue. The four Cornell children, Joseph (born 1903), Betty (born 1905), Helen (born 1906), and Robert (born 1910), were all raised with great expectations. Their mother raised them with the expectation they would all be well educated, well mannered, and well married. Sister Betty was the first to develop an interest in art, so in 1913 her mother hired a local tutor to give her lessons. The fellow she hired had recently returned from training at the New York School of Art. He was a tall lanky thirty-one-year-old from Nyack named Edward Hopper (1882-1967). His father owned the dry goods store where Betty’s father worked, and from which her father had purchased the stereopticon.

Prodded by his wife to seek a more ambitious career, their father left the dry goods store and began to work on a commission basis as a traveling salesmen of woolen goods. In 1914 the family, including the mother’s parents, moved to a more stately home at 137 Broadway in Nyack. They were living a bit beyond their means, but the mother longed for the fabled comfort of her prosperous ancestors. Her eldest son, Joseph Isaac Cornell, (the fourth), was being groomed for higher education. This was the privilege of the upper class at the time, when the children of most middle class families commonly received no education beyond the eighth grade. Although their father did not earn as much as their mother would have liked, they all looked back on those early years in Nyack as idyllic.

The Cornell children spent their days playing on a spacious back yard lawn, beyond which the Palisades offered a spectacular view across the Hudson River and the faraway skyline of New York City. The family spent their evenings by the fireside reading the Holy Bible and fairy tales by Hans Christian Anderson. The father loved modern gadgets so he delighted them with magic lantern shows, Edison cylinder recordings, and newly acquired viewing cards for the stereopticon.

Along with these sweet memories there were also serious challenges, financial worries, and marital problems. By 1915 the youngest child Robert had begun to show signs of a disability that would eventually be diagnosed as cerebral palsy, which made him physically invalid and mentally childlike. Despite his condition Robert’s incredible sense of humor and complicated notions were a genuine delight to his brother and sisters.

The father began to spend more time away from the family, to earn more money on the road as a traveling salesman, but also to more freely pursue his happy-go-lucky nature. Suddenly at the age of forty-two on April 29, 1917, Joseph Isaac Cornell, III, died in a Manhattan hospital. According to a notice in The New York Times, his funeral service was held at the family home in Nyack on May 2nd at 3pm.

After this tragic loss the Cornell children felt an even greater appreciation for the sweetness of times past. There was suddenly a deeper sentimental significance attached to their magical visits by stereopticon to other worlds. Three months later as that summer ended, thirteen-year-old Joseph Cornell was sent to Phillips Academy, the prestigious boarding school in Andover, Massachusetts, where he was extremely unhappy. He lost his father, he lost his childhood, and he missed his younger siblings, about whom his entire world had always rotated. It was as though he had suddenly been banished by some higher authority from everything he loved. His mother sold the family home in Nyack and moved with Betty, Helen, and Robert to an apartment on First Street in Flushing, Queens, where she lived from family savings in retirement at the age of thirty-three. She still had her great expectations for Joseph to graduate Phillips Academy and go on to an Ivy League college and start some prosperous business career.

Instead of marching in step to his mother’s drumbeat, Joseph Cornell failed to thrive at the school. He stayed there for four years until June of 1921. At the age of seventeen he left the school without having passed enough classes to qualify for a high school diploma. He moved in with his family in Queens and soon entered the work force. His mother found him a job through his father’s old business connections. He was hired as a salesman of wholesale textiles for the New York City garment industry. His modest salary supported the family. As soon as she was old enough, sister Betty went to work as well. Joseph Cornell accepted his fate with silent resignation. He had missed out on a few important things. He had missed out on four years of childhood with his siblings. He had missed out on teenage dating. He had missed out on going to an Ivy League college. He had also missed out on one of his most cherished dreams, which was to have been rewarded for graduating college with a trip to Europe. Many American kids in the roaring twenties still considered the Grand Tour of Europe as the maraschino cherry that topped off their worldly education. But all Joseph Cornell would ever see of France were three-dimensional views on his stereopticon, which he studied in minute detail.

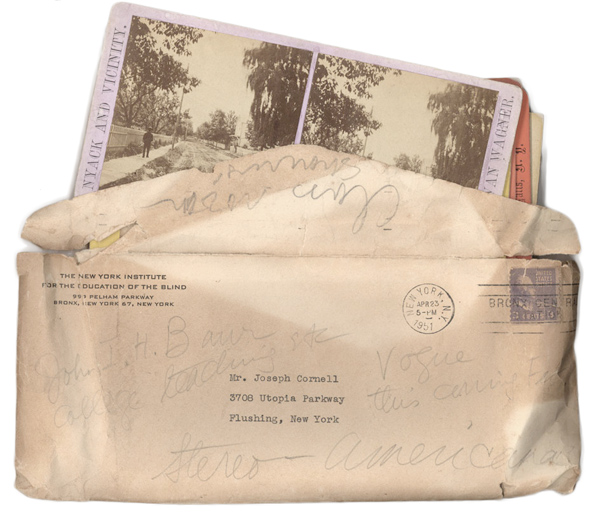

By 1927 the family could afford to pay a mortgage on a modest two story home at 3708 Utopia Parkway in Flushing, Queens. By that same time sister Helen had grown up and married and moved away to Long Island. Her departure left Joseph and Betty more aware of the seriousness of their situation and their shared responsibility to support their mother and brother. Although it was awkward to talk about, Joseph told Betty she should feel free to also marry and leave home someday, because he volunteered to stay home for the rest of his life.

According to Freud it is natural to feel an infantile sense of abandonment when one’s father has died. It is also natural for the eldest son to take on some of the father’s responsibilities towards his younger siblings, especially if one is disabled, but Joseph Cornell took on a bit more than a healthy share of family responsibilities. Maybe he did this as a roundabout way to defy the higher authorities that had made him feel so abandoned and banished. Whatever it was, something made Joseph Cornell extra sensitive about protecting discarded things, even the homeliest detritus from the littered streets of New York City, which he carefully rescued and preserved in teeming folios that eventually overwhelmed every room in his house and became a massive archive of ephemera that he endlessly sorted into complex and poetically associative folders. Along with collecting books, magazines, prints, photos, and posters, he also brought home new stereopticon viewing cards. Much of this material was purchased from second hand bookstores, which he visited while walking along his routine beat through Manhattan’s garment industry. For the next few years Joseph and Betty cut out pictures from magazines and made scrapbooks for Robert’s amusement, on the pages of which he drew imaginary creatures in wonderland scenes.

During this desperate period, before the Great Depression would bring even harder times, Joseph Cornell still showed no interest in making art. But he did bring home a lot of things that would eventually become his art materials, and he spent a lot of time in a magical neutral zone playing with Robert and the stereopticon, navigating reality somewhere between his mundane life and his younger brother’s innocent reckonings. And then suddenly in 1932 Joseph Cornell began to make art. At first he made mysterious objects, which were handheld enigmatic toys for inexplicable parlor games.

During his workweek rounds of New York City garment factories he also wandered into museums and art galleries, such as the Julien Levy Gallery on 57th Street, where Surrealist art was championed. This incredibly perceptive gallery owner had noticed his shy visitor before, so he asked if he was an art collector or an artist. Upon seeing Cornell’s work Levy instantly invited him to join an upcoming group show, which officially launched his art career.

Many of Europe’s greatest artists had come New York City in the 1930s. The privilege of mobility came in pretty handy during the desperate flood of refugees fleeing the nightmare of Nazi Germany. Surrealists in exile found a welcome venue at the Julien Levy Gallery. Another instance of this art dealer’s sensitive insight was to introduce Joseph Cornell to Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968). After their first meeting Duchamp recounted to Levy a puzzling story. Cornell had spoken to him in French about Paris and the Place de l’Opera, the Musee du Louvre, and the Grand Hotel, but eventually mentioned he had never been to France, which mystified Duchamp. Did Cornell have some extrasensory power that permitted him to discuss the streets of Paris as though they were his old haunts? No. It was just the magic of the stereopticon. With the intensity of an autodidact Joseph Cornell had squeezed his never-to-be Grand Tour of Europe from a fascinated scrutiny of well-thumbed stereoscopic viewing cards.

The two artists became life long friends and mutual admirers. They worked together on several creative projects, exhibitions, and publications. Duchamp’s historic valise project was designed with Cornell’s boxes in mind, and a portion of that complex project was assembled by Cornell. It is curious to consider how both artists shared the same stereoscopic sensibility. Perhaps it was a tendency of their generation, which came of age in an era of scientific wonders, but Duchamp’s most important pieces all reflect the visual experience of the stereopticon. He was fascinated with quasi-scientific optical machinery, such as his rotoreliefs. His most important work The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors Even (1923) was first explored by an earlier piece To Be Looked At With One Eye, Close To, For Almost an Hour (1918). Even his first groundbreaking artwork in the sensational Armory Show of 1913, The Nude Descending a Staircase (1912), is like an illusion of form that is struggling to come into focus somewhere between two and three-dimensional space. Duchamp’s late masterpiece, permanently installed in the Philadelphia Art Museum, is a clear homage to the magical world of the stereopticon. Given The Illuminating Gas and the Waterfall (1966) is yet another mysterious object made of wood with two eyeholes, through which to glimpse a startling three-dimensional dreamscape.

Joseph Cornell’s stereoscopic sensibility also influenced his unusual approach to filmmaking. His movies splice together a wild assortment of inspiring and mundane images to create a strand of non-narrative, non-literal, and non-linear associative linkages. The experience of watching his movies is a lot like flipping through a random stack of stereoscopic views. Hypnotically nibbling visual bon-bons for a dreamy idle hour. His movies were highly successful as evening parlor games in the Cornell home with soda and popcorn. They were also appreciated at the Julien Levy Gallery, where during one showing Salvador Dali (1904-1989) outrageously interrupted the projection to stand up and scream, “I made that!”

There are many shared sensibilities among Surrealists, but when any two artists address the same subject, each one’s viewpoint will always reflect their own unique orientation. Joseph Cornell’s fundamental view of art was inspired by poignant childhood experiences of looking at stereoscopic views of a supposedly real world. Julien Levy was apparently on Joseph Cornell’s wavelength when he sent a thoughtful gift from France of a stereoscopic card from a Parisian print shop. He inscribed it with instructions to “look against infra-red,” because the viewing card had hidden interior tissues with vivid hand-coloring that was only visible with backlit illumination, but Julien Levy went one step further into the surreal by suggesting the use of spooky infrared lighting.

The 1939 New York City World’s Fair was staged in Flushing, Queens, where it attracted millions of visitors from across the seven seas. In many ways it was the major turning point in the maturity of Joseph Cornell’s art and outlook on life. If the stereopticon views from the 1900 Paris International Exposition first inspired his artistic vision, then the sight of its rebirth magically roosting in his own back yard must have been a rather strange experience for him, because it was a crystallization of his unique orientation.

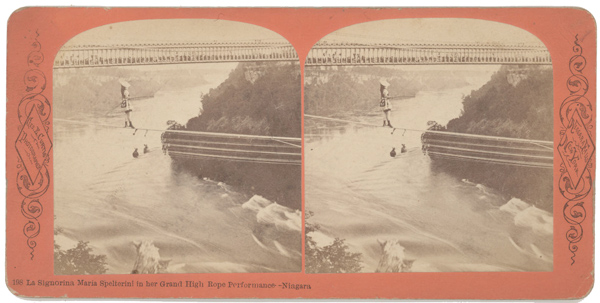

Possibly the highest point in Joseph Cornell’s art career came in January 1943 when he was invited by Charles Henri Ford (1913-2002) to produce the Americana Fantastica edition of the important Surrealist magazine, View. The cover featured a dizzying spectacle of tightrope walkers crossing Niagara Falls. These images were generated by photostat enlargements of stereopticon viewing cards in the artist’s collection. Tightrope walkers crossing Niagara Falls was a popular stereoscopic subject, because the scale and depth of such scenes are particularly vertiginous.

It is also interesting to consider that Joseph Cornell’s first inklings of life’s awesome mystery and first voyages to other worlds were stimulated by a quasi-scientific device. In a similar way he and sister Betty were fascinated with Astronomy and the Natural History Museum. But more than that, they were devoted followers of Mary Baker Eddy’s philosophy of Christian Science, a spiritual faith in God’s unknowable but supposedly astrophysical power. They believe in the restorative powers of prayer, entranced in a silent mindful stillness, to bring a troubled spirit back into harmony with the universe. To believe that atomic particles are the essence of the Holy Ghost adds a deeper reverence to clairvoyant inklings, and a possibly profound significance to everything serendipitous. Joseph and Betty were exceptionally attuned to both of these phenomena.

As fate would have it, the Hollywood movie star Tony Curtis (1925-2010) eventually became a close and trusted friend of the Cornell family. He was probably onto something when he said that much of Joseph Cornell’s inspiration was geared towards a lifelong need to provide fascinating amusements for his invalid brother. This idea adds even more importance to the role of the stereopticon in the family’s interwoven health.

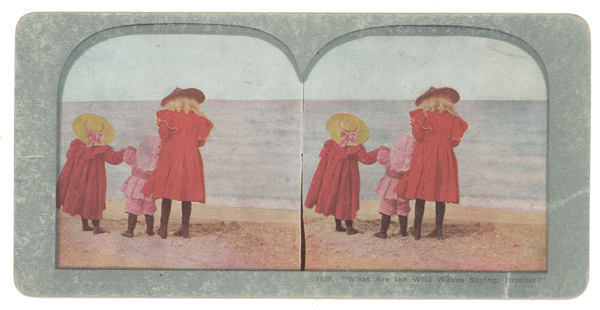

In the summer of 1983 Tony Curtis sent Betty a special greeting card. It was a stereoscopic view of three children facing the vast and mysterious sea. It was titled, “What Are The Wild Waves Saying, Brother?” Betty was thrilled to see such a miraculously poignant reflection of her own childhood with Joe and little Robert.

Joseph Cornell’s stereopticon is a mysterious object that in many ways was central to the unique viewpoint of this American master. The oddity of this fact becomes rather more weighty when we consider that this common novelty item creates optical illusions that were emotionally significant to the artist for thirty years before his own artistic efforts. So these are not images that he gathered together because they reflected his artistic tastes. These are images that his father brought home, and which fascinated him for thirty years, before he ever thought about making art. There is no doubt that Joseph Cornell’s stereopticon had a significant influence on the development of his artistic vision.

David Saunders is an artist (b.1954 – NYC) and was a friend of Joseph Cornell.