by Steve Turtell

“A young man must not make safe investments.” — Jean Cocteau

The immediate “yes” to David’s proposal that I help run the lights for The Palm Casino Revue became an automatic response to any suggestion that I try something new. I’d done it already when Richie proposed working as a baker at the Paradox, and again when Manuel said I could model for art classes. Looking back, I can say that over and over again, when friends and even casual acquaintances asked me if I’d like to do something, most of the time, I’ve said “yes.”

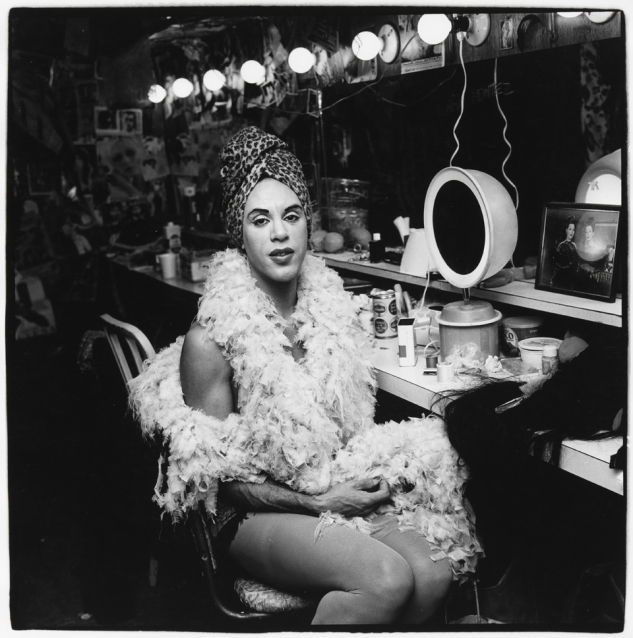

The next night, I arrived at the theater two hours before curtain. David introduced me to Jan Kroeze, an experienced theater lighting designer, unlike David, who mainly worked high-end residential, e.g., installing pin lights throughout the rain forest surrounding Pace Gallery owner Fred Mueller’s country house in Puerto Rico. Together they had ordered the elaborate lighting plot for the Revue—a complex mix of Fresnels and Lekos hung to provide as much variety as the acts—everything from a Folies Bergère parody, several punk rockers, a one-act drawing room mystery, pantomime, monologues, and Larry Ree, aka Madame Ekaterina Sobicheskaya, cofounder of the Trockadero Gloxinia Ballet de Monte Carlo. Larry was a 6’4” Texan who earned his living as a dresser at the Met and other venues for international ballet and opera stars. They often requested his services and a few might have been surprised to learn his opinion of them. About Pavorotti he once said to me “Yeech! all that hairy, sweaty fat!” His devotion to the ballet was so complete he’d taught himself to dance en pointe, a feat that impressed no less than George Balanchine. In toe shoes and counting his faux Russian headdress he topped out at 7 feet. Larry’s sophisticated mixture of talent, deep knowledge, camp, and determination set the tone for the entire revue.

Jan, a tall, thin, friendly, relaxed Brit who looked and dressed like every English rock star of the moment—long hair that rested gently on his shoulders, a colored shirt tucked into cuffed pleated pants—led me onstage and explained the rows of knobs and controls on the lighting panel directly behind the proscenium arch stage left, just out of view of the audience. He showed me which lights they controlled and how to turn and lock two or more knobs together to make some cues easier. Sometimes an entire row of knobs and even two or more rows were on lock, and nearly every light aimed at the stage could be raised or lowered at the same time with a single motion, allowing for gentle crescendos and sudden blackouts. Once he was sure I could follow his verbal instructions, he walked up the center aisle and climbed up to a platform at the back of the theater directly above the entrance. From there he could direct both the follow spot and read me cues via a headset. We practiced as some of the dancers from Manuel’s Girls stretched their legs around their heads and warmed up—the downstairs dressing rooms, overcrowded with more than twenty additional other performers not providing sufficient room.

I immediately fell in love with the atmosphere and the energy of performers and tech crew getting ready for a show. Jacob Burckhardt, son of the photographer Rudy Burckhardt, checked the mics and sound levels; Jan and I ran through the lights and made sure none of the lamps had blown or any of the gels had slipped from their frames; Steve Lawrence, editor of Picture Newspaper and soon to be art director for the New York Times Magazine, had designed the minimal sets and checked for damage. Sheyla, producer, seemed to be everywhere at once, while Adrian Milton, stage manager, gave periodic time calls: Half hour to curtain, fifteen minutes to curtain.

At the five-minute call I tried to relax but was both anxious and thrilled. Ten couples were onstage under a forest of tiny spots (Cue No. 1) waiting to start swaying to the opening bars of Begin the Beguine played by Juilliard graduate Norman Rollins, a barrel chested piano player with a backstage rep as a slightly kinky hottie and a thriving practice as a vocal coach in his apartment in the Ansonia. He had a handlebar moustache just like Nietzsche’s and one of those hard, muscular bodies I always went for. Sometimes he wore overalls with no shirt or suspenders that covered his nipples or a form-fitting long-sleeved undershirt. He knew his audience.

Norman vamped a dramatic intro as the house lights went down and then segued into the Cole Porter classic while Sheyla’s Portuguese boyfriend Antonio sang and the couples fox-trotted their way across and off the stage. The stage lights came up and the show began, as former Cockette John Flowers slithered down the narrow center aisle in skin tight satin while he belted out Devil With The Blue Dress, Blue Dress, Blue Dress, Devil With The Blue Dress On. Flowers, a talented artist, had designed many of the Cockettes’ sets, posters and handbills. He also did the artwork for the only publication by the troupe, a gender-bending paper-doll cutout book for which they modeled. His simple but boldly outlined drawings antedated Keith Haring’s similar style by nearly a decade. In the book, the name of each member of the Cockettes was surrounded by the same lines Haring used repeatedly in his iconic Radiant Baby. Flowers once defined the aesthetic of the Cockettes very succinctly: “Glitter covers a multitude of sins.”

After the opening numbers, for the next two hours, or sometimes three, the audience was treated to a variety show unlike any other I’ve seen before or since. Take a big slice of vaudeville, top with a hefty dollop of musical comedy, add in some thrift-shop, nineteen-thirties Hollywood glamour, season it with early punk rock and the nascent, Lower-East-Side art scene which was already percolating, cast it with every energetic, talented performer around via La MaMa, CBGB’s, Charles Ludlam’s Ridiculous Theatrical Company plus half a dozen East coast transplants from San Francisco’s Cockettes, throw in a few legendary downtown drag queens including Mario Montez, the off-off-Broadway legend and underground film star of Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures and Normal Love, and you’ll get some idea of the wild ride that the Palm Casino Revue gave to its lucky audiences for forty performances in the late spring of 1974.

Highlights included Future MANIC PANIC founders Tish and Snooky, Tomata du Plenty and Gorilla Rose. Former Cockettes Fayette Hauser and Sweet Pam (Tent), who changed her name to Paula Pucker for a while, sang the blues. Alexis del Lago unraveled the secrets of a movie star’s confused dream in a sometimes equally confusing monologue; Manuel and His Girls’ (many of whom had performed with companies like the New York City Ballet and the Alwin Nikolais Dance Theater, where Manuel had been a principal dancer) made fun of loose pasties and looser limbs in a frenetic, hilarious Folies Bergère parody. As soon as she finished performing Prudence in Camille with the Ridiculous Theatrical Company, Lola Pashalinski ran down from the Evergreen Theater, put on a tux and sang The Most Beautiful Girl in the World—to this day my favorite rendition of that song. The range of talent on display was thrilling and it’s not an exaggeration to suggest, as one scholar has, that the Revue “anticipated the ascendency of cabaret as a principal mode for performance art in the East Village during the 1980s.”

It was a scene. Diana Vreeland came with Cecil Beaton but almost didn’t get in until someone recognized them. Baby Jane Holzer made an appearance. Debbie Harry hired Tish and Snooky to sing backup with Blondie. In his memoir, CBGB founder Hilly Kristalin called the Revue a “wacky, campy, rock revue.” You never knew when Christa and Jose Arango’s offstage drama would threaten to spill onto the stage or Jose would be too drunk to perform, or when Larry Ree, aka Madame Ekaterina Sobicheskaya, would scare the shit out of the innocent filmmaker someone had invited downstairs and who was “stealing” Larry’s image and act without his permission. Act Two opened with a one-scene Halloween Murder Mystery set in a drawing room (which may have been the inspiration for Hilly Kristal, to bring it across the street to CBGB’s on Halloween).

The Mystery, in fifteen packed minutes, featured John Flowers, now a sedate maid cleaning up the room, a talking Hat Rack and several living portraits, Gorilla Rose among them. There were two blackouts and several murders prompted by, of course, a contested will. At one point, cowardly José used Fayette Hauser as a human shield. At the end, four people confessed. Finally, the true murderer was revealed: The Hat Rack, played by John Edward Heys. But before the audience discovered the evil lurking in the sedate, two-armed, oddly loquacious piece of furniture, Adrian, the stage manager tossed a revealing clue out from within the fake fireplace. He was often so drunk that he came out with the prop he tossed—the audience cheered. I was so drunk I sometimes took a cab back to my apartment ten blocks away, which I remember chiefly because of the conversation I had with Gore Vidal one night. Gore was not in the cab with me, but I needed him to know that once we were better acquainted he would not like me “because I’m a drunk and prone to sudden religious conversions.” That necessary event was not to happen for nearly a decade.

When the run was over, Jan Kroeze asked me to stay at the theater for the next show, a revival of Jackie Curtis’s Glamour, Glory and Gold: The Life and Legend of Nola Noon, Goddess and Star! directed by Ron Link and featuring Madeleine le Roux, star of Tom Eyen’s camp classic The Dirtiest Show in Town. We used the same lighting plot. My favorite moment was the afternoon a New York Times critic came and one of the actors disappeared at intermission, forcing the others to divvy up his lines and somehow keep the play going.

By September I was keeping the spotlight on Charles Ludlam’s hairy chest in Camille and had re-enrolled at Brooklyn College as a theater major—the idea of art restoration now receding in the rear view mirror as fast as Paul, that affair having fizzled out—(my fault, not yours Paul!). I’d never had so much fun while working before, but then, until The Palm Casino Revue, it had never occurred to me to think that work could be fun.

Steve Turtell is a poet and writer from New York City. His first collection, Heroes and Householders (Orchard House Press, 2007) drew praise from Marjorie Perloff; his chapbook, Letter to Frank O’Hara (P&Q Press, 2000) won the 2010 Rebound Prize from Seven Kitchens Press. “The Palm Casino Revue” is from his work in progress Fifty Jobs in Fifty Years: A Working Tour of My Life. Visit his website at sturtell.com.

Author’s photo by Orestes Gonzalez